Managers and leaders in search of improvement for themselves and their businesses can go to two different markets: the Knowledge Market and the Skill Market.

Managers and leaders in search of improvement for themselves and their businesses can go to two different markets: the Knowledge Market and the Skill Market.

While the commodity in the Knowledge Market is information (for more about the Knowledge Market click here), in the Skill Market people trade in results.

You can see this in the typical tests for the two. You would test somebody’s knowledge by asking them questions to find out how much information they know. You would test somebody’s level of skill by asking them to do something and create a result, whether that is building a wall or turning around a multi-million dollar business.

The vast majority of the money spent training leaders and managers – including a substantial chunk of the $104.3 billion North America invested in training as long ago as 2009 – is spent in the Knowledge Market.

By contrast, only a tiny fraction of all the leadership and management development out there (including coaching, classroom based study, e-learning, business school seminars, platform speakers, and everything else) services the Skill Market. This is one reason why senior managers are often wary of training – usually they’ve already got the knowledge. They’ve worked out what needs to be done, and assembling more information about what good managers do, or don’t do, is only of marginal use to them.

From Tell-Me-Something-I-Don’t-Know to Where-Do-I-Sign-Up?

Here is a list of advice for how the CEOs of small businesses should manage themselves to ensure they are contributing everything needed for success, taken from a book:

• Do what you love

• Eat well, sleep well, take regular exercise

• Have a positive mental attitude

• Take massive action

• Organize yourself

• Decide what you should stop doing

• Have an action plan

• Have a diary

• Work on the business, not just in it

• Have a filing system

• Set priorities and stick to them

• Eliminate distractions

As we mentioned in our article on the Knowledge Market, this list is unsurprising. If you happened upon someone selling this in the Knowledge Market, you probably wouldn’t pay them much for it. You already know this information.

If you’re shopping in the Skill Market, the list starts to look much more interesting. If what’s on offer isn’t knowledge that we should eat well, sleep well and take regular exercise, but skill at actually doing so over a sustained period, then the value shoots up. Because, of course, so does the difficulty. For every person who can tell us to look after our health, how many can actually give us the understanding and conviction to do it? How much would the British National Health Service pay to anyone who could actually develop this skill in others? And this is just one item on the list.

This is the nature of the transition from the Knowledge Market to the Skill Market: ideas go from tell-me-something-I-don’t-know to where-do-I-sign-up?

If you are investing in leadership and management training, here are some clues that the person you’re talking to operates in the Skill Market…

1. Their whole focus will be on results

Just as you can’t learn to be a better bricklayer without building some walls, it’s difficult to develop or refine management skill without creating results. In fact, the whole activity of a manager might be characterised as a process:

A) Get information

B) Take decisions

C) Mobilise self and others to create results

D) Repeat

What the information is, and what the manager decides to do, depends on their business and seniority. Naturally, a development programme should work like any other business project:

A) Get information on leadership and management

B) Take decisions

C) Mobilise self and others to create results

D) Report results to your group and repeat

Here again, what the manager decides to do and what results he or she creates depends on their business and seniority. Here are examples of typical results reported during development programmes:

After one day, a Works Manager for a metals wholesaler reported this result:

A large area of the warehouse was regularly left in an untidy state, so the manager delegated the responsibility for keeping this part of the shop floor in order to one of the workers. So skilful was the manager in doing this that the worker not only tidied the area, but has also made this part of the warehouse his domain. If anyone else leaves this particular zone in a mess, the worker goes after them and ensures it’s tidied up. This, the manager said with some surprise, has turned out to be a long-term solution to a recurring problem.

After two days, a Sales Team Manager for an electronics wholesaler reported this result:

The manager ran an appraisal with a direct report who in some respects had been difficult to manage before. The manager ran the appraisal skilfully enough to unlock the direct report’s ideas, and release new motivation.

Among other things, the manager found out the direct report did not want to move from being a salesman to being a sales manager. Again, skilfully recognising the direct report’s ideas about the future, the manager persuaded him to reconsider the merits of taking on management responsibility. They agreed new objectives to manage certain aspects of the direct report’s behaviour, and he also agreed to work with the new starters in the team.

You might observe that simply running an appraisal meeting more skilfully than before is not in itself a result. We had to wait until the fifth day of this programme to hear what the full effect of this appraisal meeting had been:

The sales team manager agreed a new structure with his boss, where the manager acquired four extra direct reports and successfully promoted a new team leader. This new team leader was the person who had attended the appraisal mentioned above, and who was now motivated to take on a position he had previously not wanted to occupy.

After three days the Sales Director of a software company reported this result:

Prior to attending the programme his sales style had been to visit a client, show them a lot of slides about his products, and ask “what do you want to buy from what you just saw?”

After attending three days of the programme he tried a different approach, finding out a customer’s needs before showing them what he had to offer. The customer outlined their requirement in some detail, allowing the Sales Director to address their concerns. As this process went on, the customer became more and more convinced that the sales director knew what they needed and could help. A few days later the customer placed a significant order.

By the end of a programme, a National Account Manager for a party products business reported this result: “at the start of this programme I was just about on target for the year. Now I am on course to achieve 130% of it.”

Meanwhile, the Principal Consultant for an international recruitment agency commented: “This course helped me take a team that was struggling to perform and were producing average monthly results to become the leading revenue generating part of a global business.”

Although the managers above are drawn from a variety of businesses and levels of seniority, they share a common denominator: they approached typical management situations in a different and more skilful way, and created new, significant results.

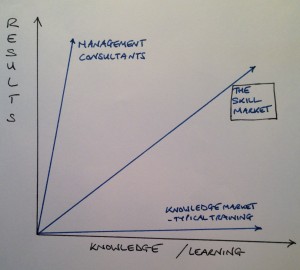

The Skill Market combines two markets that normally operate separately:

• the Knowledge Market, where people learn things and fail to create results

• and the management consultancy market – where consultants come in and create results, while the full-time employees of that business do not increase their knowledge or their ability to create results for themselves

It’s possible to map this relationship in graph form, like this:

If the people you employ learn by creating results, they are developing skills and you are operating in the Skill Market.

(For more on results click here.)

2. Robust Content

If the person you’re talking to operates in the Skill Market, the content of their seminars, coaching sessions, e-learning modules or anything else will be content that can be used by busy managers to create results like the ones described above.

There will be no management ideas that sound good in the seminar room, and have no chance of getting off the ground back in the workplace (we call these “aeroplanes made of lead” and you can find out more about them here).

They are unlikely to be using anything pulled from a shelf in the great hypermarket of management knowledge – if anyone sends you Jim Collins’ book to read before you attend their course, it’s tempting to ask “why am I going to your course and not Jim Collins’ seminar?!”

The tools they ask you to work with will be simple to understand. As you become more and more effective at management it will be your skill that will change, not the tools you are using. After all, the master sculptor and the complete beginner use the same chisel.

The Sales Director in the example above who changed his approach and secured a large order did this by simply using better open questions. These are the management equivalent of the chef’s knife or the sculptor’s chisel – cheap and readily available, they are there for anyone to pick up. They have almost no value in the Knowledge Market. In the Skill Market, they can bring in big orders, engage disaffected employees, win the support of other Board members, and more. The effective manager is simply highly skilled at using them, as well as all the other tools of her trade.

This hints at another crucial aspect – the ability to help people build real, lasting skill in using management tools is itself a sophisticated skill. As we have seen, if all that was needed was to tell someone about open questions, or any other management device, then the Knowledge Market would have done this job years ago. There is not a manager on earth who does not know what an open question is. Like a chef knowing what a knife is, the knowledge alone gives no indication of skill.

In the absence of this ability to help others build their skill at managing, the Knowledge Market turns its attention to the management tools themselves, making them look ever more complicated and technical. Like putting an iphone in the handle of our sculptor’s chisel, this doesn’t help anyone cut more sensitively.

3. Day a Month Structure

To build their skill chefs need to go and cook in the kitchen, sculptors need to go and make statues, and managers need time to go and create results. Meeting a day a month to report results fulfils this criterion, and makes the management development programme like any other business project – one that is focused on absorbing information, taking decisions, and creating and reporting results. You can find out more about this here.

4. Expert Facilitation

The person running your management development programme will need the same characteristics as the Project Director of any other business project in your organisation. Their job will be to create results working with a group of people they do not line manage.

As we mentioned above, this skill is rare, and is unlikely to be found in an academic (who of course will have other important skills that the Project Director does not share). Nor is it likely to be found in all-purpose trainers who regularly instruct others in a wider range of skills such as IT, Health and Safety etc. Most people who work in areas where an increase in knowledge directly leads to an increase in skill find it difficult to make the transition to effective leadership and management development. (Again, I’d like to stress that all-purpose trainers are likely to have skills that the Project Director of a management development programme does not share.)

The skill of successfully developing leaders and managers is rarely found in former operational managers who have retired from the hustle and bustle of daily corporate life and now want to spend their time sharing their experiences and helping others. Truly developing leaders and managers is as exhausting as any other business pursuit, especially as the former Finance Director (now management coach) will have to influence without the authority to which she has become accustomed. The assurance that “I’ve run training before” usually means the person has transferred knowledge, and that is what they intend to do on this occasion also.

The skill of developing managers through results is its own vocation, and although it would be false for us to claim that developing this skill is necessarily more demanding than acquiring any other, it certainly takes no less patience, dedication, and determination.

Qualifications

A final note on qualifications, as these quite rightly draw the attention of conscientious people searching for serious input. Operators in the Skill Market are unlikely to offer these, as they are usually awarded based on the acquisition of knowledge: you got your certificate because you sat through a certain number of seminars, or online learning events, about a pre-set group of topics, answered some questions or made a report or wrote an essay, and passed an assessment. Skill is only built through creating results (doing), which leads to an unanswerable question:

What results would you want to see before awarding a management qualification to a Sales Team Manager at an electronics wholesaler? What about a Works Manager for a metals wholesale business, or the Principal Consultant for an international recruitment company? Results like the ones detailed in the Results section above? More? Less?

* * * * * *

Training and development is often seen as a discretionary spend, and if you are shopping in the Knowledge Market that is exactly how they should be seen: as an extra, a nice-to-have, maybe even a reward for someone who has worked hard, like a trip to see an interesting film.

If you are buying in the Skill Market, development links directly into the central activity of your business. Rather than a frippery, it is simply something else you can deploy to achieve what you want to achieve. This is why turnaround CEOs spend scarce company resources on training from the Skill Market, and why CEOs growing ambitious businesses also divert funding to this area – because how quickly they grow will depend in large part on how skilful their managers are. These people want results, and if you’re shopping in the Skill Market that’s what you’ll get.

This post originally appeared on www.mitchellphoenix.com in 2013